Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Rep. Tim Murphy On The Rights of the Mentally Ill

Congressman Tim Murphy (PA-18) gave an amazing speech on (Tue. 7/29)

Text of speech on House Floor

“Mr. Speaker, the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act reforms our broken and harmful mental health system. Here are some reasons why we need it.

For some who are experiencing the most serious mental illnesses, like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, they don’t think their hallucinations are real; they know they are real. Their illness affects their brains in such a way that they are certain, beyond all doubt, their delusions are real. It is not an attitude or denial. It is a very real brain condition.

With that understanding, we are left with a series of questions: Do these individuals have a right to be sick, or do they have a right to treatment? Do they have a right to live as victims on the streets, or do they have a right to get better? Do they have a right to be disabled and unemployed, or do they have a right to recover and get back to work? I believe these individuals and their families have the right to heal and lead healthy lives.

But they are sometimes blinded by a symptom called anosognosia, a neurological condition of the frontal lobe which renders the individual incapable of understanding that they are ill.

Every single day, millions of families struggle to help a loved one with serious mental illness who won’t seek treatment. Many knew that Aaron Alexis, James Holmes, Jared Loughner, Adam Lanza, and Elliot Rodgers needed help.

Their families tried, but the individual’s illness caused them to believe nothing was wrong, and they fought against the help. These families watch their brother, their son, or their parent spiral downward in a system that, by design, only responds after crisis, not before or during. The loved one is more likely to end up in prison or living on the streets, where they suffer violence and victimization, or cycle in and out of the emergency room or commit suicide.

In a recent New York Times article about Rikers Island prison, they report that over an 11-month period last year, 129 inmates suffered injuries so serious that doctors at the jail’s clinics were unable to treat them; 77 percent of those inmates had been previously diagnosed with mental illness.

Rikers now has as many people with mental illness as all 24 psychiatric hospitals in New York State combined, and they make up nearly 40 percent of the jail population, up from about 20 percent 8 years ago.

Inmates with mental illnesses commit two-thirds of the infractions in the jail, and they commit an overwhelming majority of assaults on jail staff members. Yet, by law, they cannot be medicated involuntarily at the jail, and hospitals often refuse to accept them unless they harm themselves or others.

Is that humane? Shouldn’t we have acted before they committed a crime to compel them to get help?

According to the article, correctional facilities now hold 95 percent of all institutionalized people with mental illness. That is wrong. Yet with all we know about mental illness and the treatments to help those experiencing it, there are still organizations, federally funded with taxpayer dollars, that believe individuals who are too sick to seek treatment will be better off left alone than in inpatient or outpatient treatment. It is insensitive. It is callous. It is misguided. It is unethical. It is immoral. And Congress should not stand by as these organizations continue their abusive malpractice against the mentally ill.

The misguided ones are more comfortable allowing the mentally ill to live under bridges or behind dumpsters than getting the emergency help that they need in a psychiatric hospital or an outpatient clinic because they cling to their fears of the old asylums, as if medical science and the understanding of the brain has not advanced over the last 60 years.

We would never deny treatment to a stroke victim or a senior with Alzheimer’s disease simply because he or she is unable to ask for care. Yet, in cases of serious brain disorders, like schizophrenia, this cruel conundrum prevents us from acting even when we know we must because the laws say we can’t. We must change those misguided and harmful laws.

The system is the most difficult for those who have the greatest difficulty. Why are some more comfortable with prison or homelessness or unemployment, poverty, and a 25-year shorter life span?

I tell my colleagues: Do not turn a blind eye to those that need our help. The mentally ill can and will get better if Congress takes the right action.

Tomorrow, Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson of Texas and I will hold a briefing at 3 p.m. on the rights of the seriously mentally ill to get treatment. I hope my colleagues will attend and understand that we have to take mental illness out of the shadows by passing the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, H.R. 3717, because where there is no help, there is no hope.”

Nothing about us without ALL of us! Treatment Before Tragedy is the Civil Rights Movement of our day, a Right to Treatment and a right to Treatment Before Tragedy. Please help us reach members of Congress by going to our page and sending an email through PopVOX. It's just a few clicks! We appreciate your help and it is one way you can send a message to congress that you support HR 3717 that would stop wasteful spending of your tax dollars! http://www.treatmentbeforetragedy.org/advocate.html

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Treatment Before Tragedy is launched July 20, 2014

For the past year and a half, I have been honored to worked with a courageous group of family members and community leaders to create a new national organization called Treatment Before Tragedy, or Tb4T.

Treatment Before Tragedy members live with the consequences and impacts of untreated mental illnesses every day, and understand mental illness to be a brain disease requiring significantly more medical research. We believe that serious mental illness should receive medical treatment as a physical, medical illness of the brain, not a behavioral disorder.

Treatment Before Tragedy’s members strongly advocate for significant changes in our nation’s approach to the care and treatment of those with serious brain diseases. We support H.R. 3717, the “Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act,” which seeks to improve the nation’s broken mental health system by refocusing programs and resources on medical care for patients and families most in need of services.

Please follow us on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/TreatB4Tragedy

Please join us on our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/treatmentbefore.tragedy

For more information, please go to: www.Treatmentbeforetragedy.org

For more information, please go to: www.Treatmentbeforetragedy.org

Or contact one of

Treatment Before Tragedy’s Interim Board of Directors:

·

Asra Nomani,

304.685.2189, anomani@treatmentbeforetragedy.org

· Joe Bruce, 207.672.4449, jbruce@treatmentbeforetragedy.org

· Pam Norick, 301.332.3639, pnorick@treatmentbeforetragedy.org

Sincerely, GG Burns ~ Kentucky MH advocate

Cofounder: http://treatmentbeforetragedy.org/

Mental health programs closing across Kentucky by Mike Wynn|courier-journal.com

This report written by Mike Wynn, mwynn@courier-journal.com

sheds light on just one of the consequences of Governor Beshear's 2010 plan to save $142 million in the cash-strapped Medicaid program within Kentucky's $6 billion Medicaid budget.

I have overhead KY Behavioral Health leaders share with advocates, "We do not know how to help individuals with serious brain diseases, (mental illnesses) who want help, who are willing to participate in their own recovery – much less those who have anosognosia (lack insight to their symptoms) and refuse treatment, yet end up taking up large amounts of state funds revolving in and out of expensive inpatients beds or jail. What is the most humane solution and should Medicaid pay for some illnesses but neglect our state's most vulnerable? GGBurns/advocate.

But even after 13 years, Moore still worries he could slip back into despair without services like Recovery Zone, a therapeutic day program he attends in Louisville for adults with debilitating mental illness.

Without the program, "I wouldn't have anything to do," he said. "And you can get into trouble ... when you have a mental illness and there is nothing to do."

For many adults with severe and chronic mental disorders, access to such daytime therapeutic services is on a steep decline in Kentucky, leaving what some fear is a gap in care that isolates the mentally ill at home or drives them out into the streets, hospitals or jail.

The Kentucky Association of Regional Programs reports that 33 of the roughly 50 programs offered across the state have closed in the past 18 months while four others have reduced their hours by half.

That reflects a shift away from using day programs in the field of behavioral health that community mental health centers must embrace, according to the Kentucky Department for Behavioral Health, Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities.

But advocates also say the centers have struggled to get enough coverage authorized under Kentucky's Medicaid managed-care system to keep the services operating. That has forced programs to close before new services are available to replace them, they argue.

Steve Shannon, executive director of the regional programs group, estimates that closings have impacted more than 1,000 people statewide — many suffering with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bi-polar disorder or major depression.

At Seven Counties Services, the community mental health center for the Louisville region, three day programs were consolidated into one this year, scaling back services for 70 to 90 clients in Bullitt, Spencer, Shelby, Henry, Oldham and Trimble counties.

Recovery Zone in Louisville is now the only traditional therapeutic recovery program offered through the center, although Seven Counties has launched alternative recovery programs in the affected counties.

Bluegrass.org, the mental health center for 17 counties in Central Kentucky, shuttered all five of its day programs last year, each closure affecting about 35 clients.

Kelly Gunning, an advocate from the Lexington chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said those closures hit many communities hard.

"People that had a place to be in the day no longer had a place to be," she said. "We don't know where they were. They certainly weren't engaged in any therapeutic rehabilitation at that point."

Even when programs are doing well, some patients aren't getting access, according to care providers.

At Bridgehaven, which offers psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery services in Louisville, about two dozen clients either had to discontinue programs or were turned away in the past 18 months because of problems getting the services authorized through Medicaid managed-care, said Ramona Johnson, the organization's president and CEO.

Recovery or status quo?

Therapeutic rehabilitation programs typically involve a mixture of group therapy, life skills training, and professional assistance with symptoms and medication management.

Clients attend several days each week, providing a full day of interaction with therapists, social workers and others with mental disorders.

Gunning said families count on the programs for respite, and for people with severe mental illness, they provide "someplace to be, something that gives meaning to them."

Dennie Carpenter, a 54-year-old with schizoaffective disorder who participates in Recovery Zone, said the program has been a "life saver" and that interacting with others reminds him that he is not alone with his illness.

"When they cut programs like this, you go home and you just dwell on negative thoughts," he said. "The next thing you know, you get angry. And the next thing you know, it can get out of hand."

Yet, according to Dr. Allen Brenzel, medical director of the Department for Behavioral Health, the field of behavioral health has been shifting away from day programs, which he described as an indefinite intervention that "actually leads people to staying in the status quo."

Brenzel argues the field has become more focused on "recovery oriented" models that emphasize vocational rehabilitation and seek to keep people living and working in the community rather than congregated in a single setting.

Every center in Kentucky received state funding in 2013 to set up new services such as case management, job coaching, in-home support and psychiatric aid, he said, adding that the goal is to push intensive services out to the patient rather than bringing them into facilities and day programs.

"I'm optimistic that we are building a more robust system with a greater variety of services that match the individual's needs rather than making the individual match what we offer," Brenzel said.

Still, critics say there's been no policy discussions about discontinuing therapeutic rehabilitation programs or any coordinated effort to ensure a successful transition.

Instead, they argue that services previously covered under Medicaid were increasingly denied after Kentucky expanded Medicaid managed care in 2011, contracting with outside firms to run the system and save taxpayer money.

"The programs were closed because the (Medicaid companies) weren't paying for them any longer," Shannon said. "All that took place before new services were available to meet the need."

Shannon said that while he supports the recovery-oriented service model, he questions why the state still counts therapeutic rehabilitation as Medicaid-eligible service if it wants to shift to new programs.

Paul Beatrice, president and CEO of Bluegrass.org, also said if the Medicaid companies want to shift coverage for services, they should work with community mental health centers to develop alternatives and time schedules for the transition.

"It would be nice to participate in the planning of that because it's the consumer who ends up paying the ultimate price," he said.

'OK for years'

Of the four companies that run Kentucky's Medicaid system, mental health advocates say Coventry Cares — and its subsidiary MHNet — are by far the worst about denying coverage or reducing hours for therapeutic day programs.

Coventry and MHNet are owned by insurance provider Aetna, which reported $1.9 billion in net income last year. But the company says complaints are off target and that it is committed to providing patients with high-quality care.

MHNet has approved two-thirds of the requests it received for therapeutic rehabilitation since January 2013, Aetna said in a statement.

But Shannon said that even mild reductions — such as approving services for three days a week rather than five — can wreak havoc on a program's financial viability.

He also argues that centers may have stopped requesting services once they realized that MHNet would not approve them.

Marsha Wilson, vice president of adult mental health services at Seven Counties, points out that the two programs Seven Counties closed this year "had been doing OK for years" before the changes in Medicaid.

Taking up transition

Seven Counties says it has tried to be proactive by transitioning rural therapeutic rehabilitation programs into recovery support centers, which focus on education, vocational work, peer support and community living skills.

Seven Counties has used state money for the effort since Medicaid doesn't cover the services, and about 70 percent to 75 percent of former therapeutic rehabilitation clients participate in the recovery support centers.

Kimberly Brothers-Sharp, vice president over Seven Counties' rural services, said the new programs offer fewer days and less structure than the traditional day programs but that many clients have still "benefited greatly" from the services.

In Lexington, NAMI partnered with Bluegrass.org to create Participation Station, a peer-run recovery program that provides educational and life-skills training to about 40 participants.

Gunning, from NAMI, said that effort has absorbed most of the people from the closed therapeutic rehabilitation program in Fayette County, but she cautioned that surrounding communities do not have similar services in place.

Shannon said most people who participated in the shuttered day programs are likely still receiving some form of case management and outpatient therapy.

"But they aren't getting that day program every day, and there is not someone seeing them everyday to see how they are doing," he said.

Shannon said he hopes programs like Participation Station will help replace the day programs around the state. But, he adds, it's unclear whether Medicaid managed care companies will pay for such services.

Sheila Schuster, an advocate for mental health and public health programs, warns that the state with face costs from caring for the mentally ill either way.

"You can either take care of them in an outpatient setting where they are in the community and learning a job," she said. "Or you can take care of them in an institution and we are all going to be paying through the teeth."

Reporter Mike Wynn can be reached at (502) 875-5136. Follow him on Twitter at @MikeWynn_CJ.

read more here and view videos on the Courier Journal:http://www.courier-journal.com/story/life/wellness/2014/07/18/mental-health-programs-closing-across-kentucky/12860897/

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

"lets not separate the brain from the body" ~ House Bill 527

Better strategies aimed at mental health in Ky. could improve health, economy and public policy

06/10/2014 07:55 PM

- by Jacqueline Pitts

- • @Jacqueline_cn2

- • 2 Comments

- • Filed under: From Frankfort

Knowing how to identify and properly treat mental illness could spark the single biggest shift in bringing efficiency to the health care system while improving Kentuckians lives, two experts said.

Currently Kentucky spends 4 percent of the $3 billion dollars in Medicaid managed care on mental health programs. But an estimated 40 percent of Medicaid enrollees have mental illnesses or issues — many that go undiagnosed, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid.

Kentucky, unlike states like Colorado , hasn’t tracked how undiagnosed mental health issues, like depression or bipolar disorders, fuel other medical costs or spill into the school system in the form of behavioral problems — or fill up jails and prisons.

But Rep. Jimmie Lee, D-Elizabethtown and the chairman of the House budget panel that deals with health programs, said if Kentucky can get its approach to mental health right it would have broad effects across the board.

“The savings itself would promote the expansion of the system without having any additional revenue,” Lee said (at 3:40).

Lee and Steve Shannon, executive director of the Kentucky Association of Regional Mental Health Programs, said the health care system — and government-funded Medicaid — could save money by treating patients for physical and mental issues at the same location. Shannon said it’s like the “fram oil filter” model of pay now or pay later. It is time for the mental health system to pay early to avoid later costs, he said.

“Lets pay now and lets pay less now,” Shannon said (at 4:30). “Lets look at the whole person and lets not separate the brain from the body so when someone goes, lets really understand what is happening when they see a doctor and have that doctor realize ‘maybe this person does need to see a clinician.’”

The General Assembly passed a bill this session, House Bill 527, that would allow mental health centers to provide physical care by hiring a doctor or nurse practitioner — something both Shannon and Lee believe will help. But Shannon said people with mental illness die 25 years younger than the average age of death from preventable illnesses because they don’t get the care they need.

Shannon said dollars could be spent more wisely by looking at spending in areas like the corrections system.

“How much dollars are we spending in the corrections system for folks who could be in the community, never go to the corrections system, and never be seen there but be treated here and not have a record that reduces housing opportunities and employment opportunities, all those negative consequences,” Shannon said (at 6:30).

As for how the Medicaid managed care companies are handling mental health patients, Lee said representatives from the managed care companies have told him they will be changing the way they do business because it is effecting their bottom line. (See that conversation starting at 11:00 in video above).

Other bottom lines are affected by the way the state handles mental health as well. Lee said the state will have a budget shortfall for available behavioral health funds. And Lee and Shannon agreed any money saved through efficiencies in behavioral health needs to stay in behavior health and not be diverted else where as it has been in the past.

“That’s got to stop,” Lee said (at :30 in video below). “We can not treat and work with this population if you’re not going to let me or the folks that work with these dollars to keep those dollars within this budget in order to be able to expand on what we saved.”

Read more here: cn|2 Pure Politics - Better strategies aimed at mental health in Ky. could improve health, economy and public policy

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

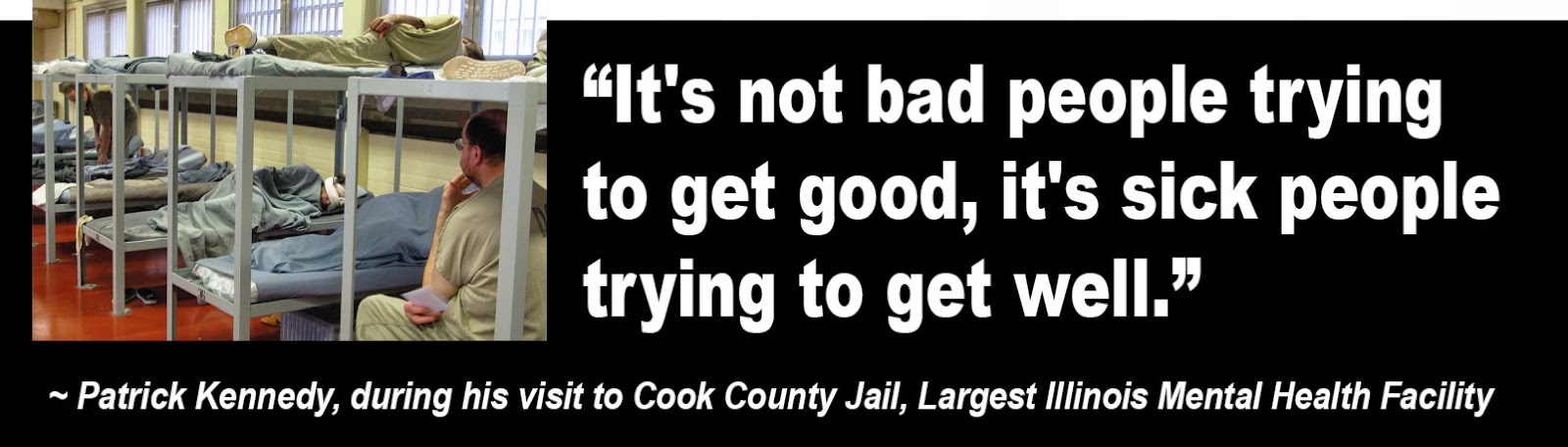

Patrick Kennedy Visits Mentally Ill Inmates Of Cook County Jail, Largest Illinois Mental Health Facility

Legislators ask, "Where do we find $$'s to monitor 'patients' who need AOT?" Disablity Rights advocates say, "It is inhumane to lock up individuals with mental illness!"

Yet places like Cook County Jail are recreating their own mental institutions ~ even growing food in gardens just like the assylms did years ago. Imagine what our world would be like if we didn't punish people for having a brain disease?

This article is a must read! http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/20/patrick-kennedy-cook-county-jail_n_3964699.html?utm_hp_ref=fb&src=sp&comm_ref=false

"The number of people here talking about hearing voices and seeing things, it's hard for me to accept that we as a society can't make a better distinction between someone who made a decision that is reprehensible and you want to punish it versus someone who is ill and acts out that illness through symptoms we deem criminal behavior. Then we treat them in a prison as opposed to where they need to be treated: in a mental health clinic."

Kennedy said improving treatment -- and ultimately, perception -- of mentally ill Americans is a civil rights issue.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)